The World Cook

Tapping into a cultural moment around the World Cup, we helped TUI launch The World Cook, a competitive international cooking series streamed on Amazon Prime Video.

We discover the breakthroughs that brands need to win. The discoveries, experiences, invention, integration and impact that will make a difference to their business. We are built to keep pace with change, built on data and technology, built for people and algorithms, built around diverse capability, built to test and learn at scale and, crucially, built to evolve.

Tapping into a cultural moment around the World Cup, we helped TUI launch The World Cook, a competitive international cooking series streamed on Amazon Prime Video.

We celebrated the speed of Google Chrome with Lil Yachty, Busta Rhymes and McLaren F1 driver Lando Norris.

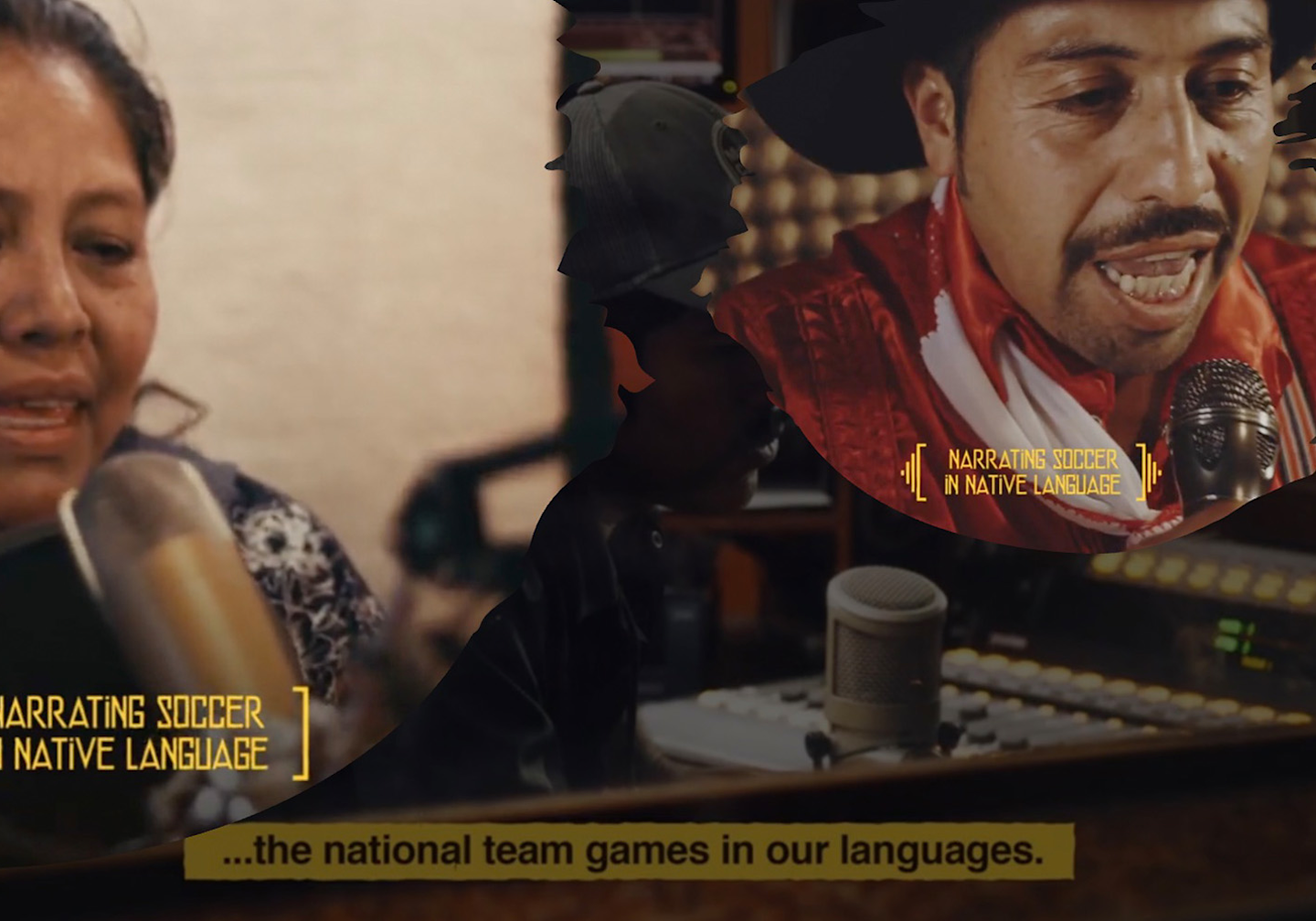

Corona trained a new generation of Mexican sportscasters to tell the story of Mexico’s final qualifying matches for the 2022 World Cup.

We launched a new campaign to stop fast fashion in its tracks.

Subway needed a breakthrough to claim their space at the head of the pack in the food eCommerce space.

With 120 offices and over 10,000 people operating in 96 markets.